"We were throwing away too many pouches at the end-of-line," the operations head at a seafood plant in Da Nang admitted. "We didn’t need bells and whistles; we needed seals that held—every shift, every batch." That was our brief to start. As the person signing the capex, I wanted one thing: predictable results without surprises. We brought **ASFL** into the conversation because the teams needed options that fit tight spaces, variable product, and impatient schedules.

Across three sites in Asia—a seafood processor in Vietnam, a boutique tea exporter in Sri Lanka, and a cloud kitchen network in Jakarta—the story began the same way: too much rework, too many complaints from QA, and no patience for experimental gear. They had read their share of **food vacuum sealer reviews** and had opinions. I care about cost per packed unit and risk. If we can’t justify it on a spreadsheet and on the floor, it doesn’t stick.

Industry and Market Context

The seafood site in Da Nang ran mixed-spec fillets with brine carryover, which loves to sneak into seal areas. Their OEE had hovered at 62%, with 7–9% of bags flagged for weak or bubbly seams. The team worked in a room that gave us barely 1.8 meters of counter length near a drain—space was our first constraint. Energy pricing was predictable; rework wasn’t. Our target was not a headline number. It was a steady, defensible climb to mid-70s OEE and fewer late-night re-packs.

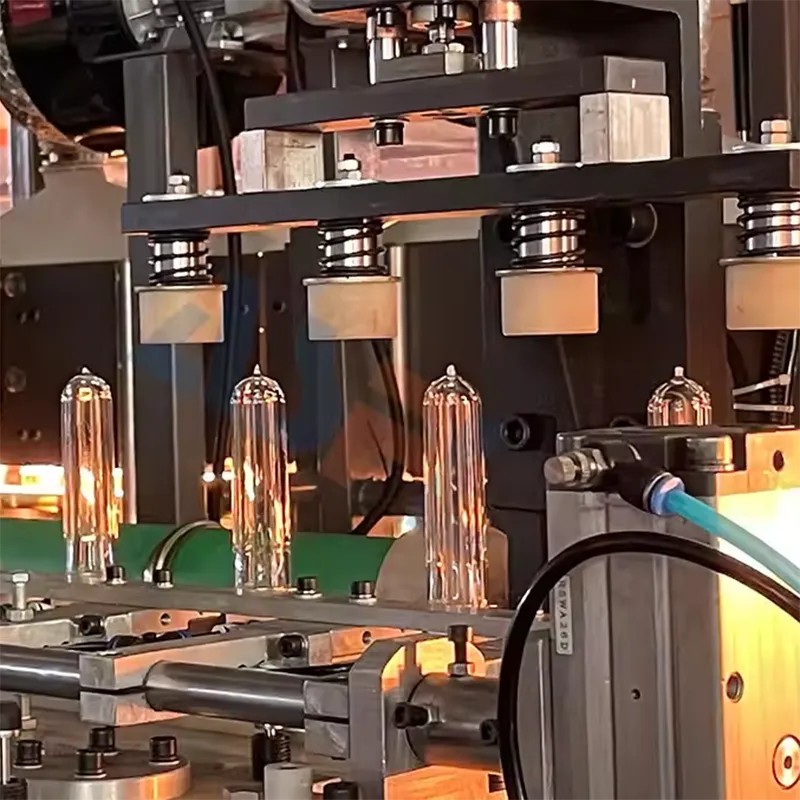

In Kandy, the tea exporter sold premium blends online. Aroma retention mattered more than raw speed. They ran small batches—often 200–300 pouches per SKU—with oxygen absorbers. When they loaded the pouches too full, we saw “seal shadows” at the gusset. That translated into 3–4% of pouches failing sniff tests in random checks. They had read **food vacuum sealer reviews**, but the nuances of a chamber sealer with gas backflush don’t show up in consumer write-ups. They needed industrial discipline on a small footprint.

Jakarta’s cloud-kitchen network was the wild card: frequent menu changes, long hours, and limited training bandwidth. They rotated staff every quarter and wanted units that were tough yet simple. During pilots, one kitchen tested **cabela's vacuum sealer bags** because they had ready access to those rolls. Texture and thickness varied by batch, which complicated sealing consistency. The mandate to me was blunt: keep consumables simple, standardize on a thickness range, and avoid lock-in that hurts the P&L.

Needs Assessment and Discovery: What Did We Overlook?

We started with a short, on-floor audit. At the seafood plant, moisture management was the hidden saboteur. We mapped their process and found a nine-minute gap between draining and sealing; condensation crept back in. A small tweak—adding a staged rack and two minutes of fan-drying—cut visible moisture at the mouth of the bag. That alone took rework down by 2–3 points before we touched hardware. It reminded me that the cheapest fix is often upstream.

Training mattered more than anyone wanted to admit. The tea line had a perfect machine on paper, yet the first pilot failed. Operators weren’t clear on how to use vacuum sealer machine settings when swapping between flat and gusseted pouches. We ran two 45-minute sessions covering fill height, lip cleaning, and vacuum levels. We standardized vacuum setpoints at −75 to −85 kPa for most teas and added a simple check: tug-test three bags per changeover. After week two, scrap dropped into the 2–3% band.

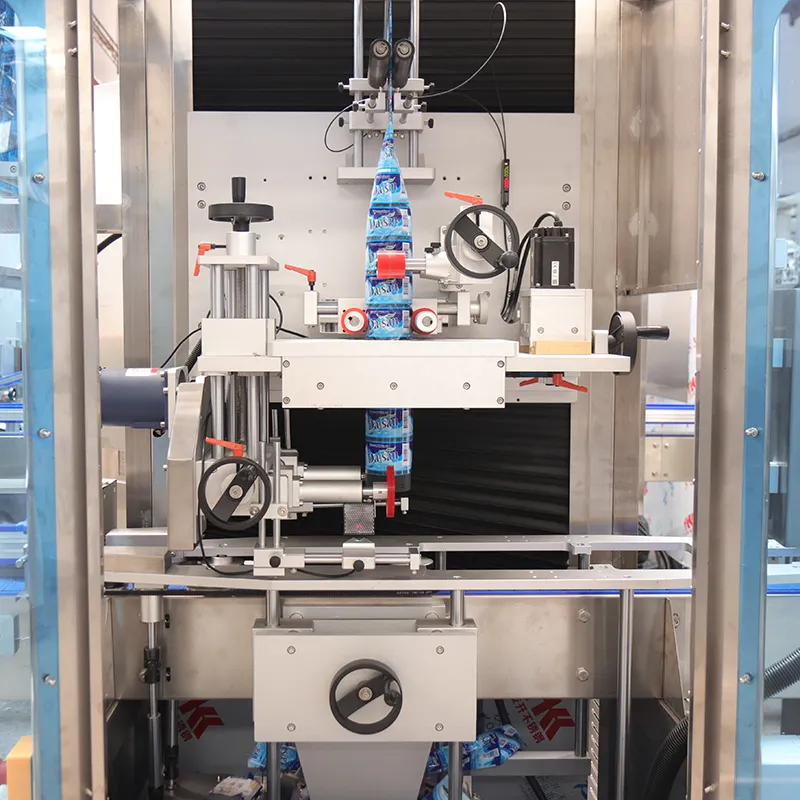

Jakarta’s kitchens moved fast. Their first run showed cycle times drifting from 14 to 20 seconds per bag because staff paused to double-check labels and portion sizes. We split the tasks: one person staged pouches, another sealed. Cycle time stabilized at 14–16 seconds. It wasn’t glamorous, but it was stable. Based on insights from **ASFL** service teams, we also added a laminated one-pager next to each unit with a three-step SOP and a photo of a clean seal we expected to see. That knocked out half the confusion.

Equipment Configuration

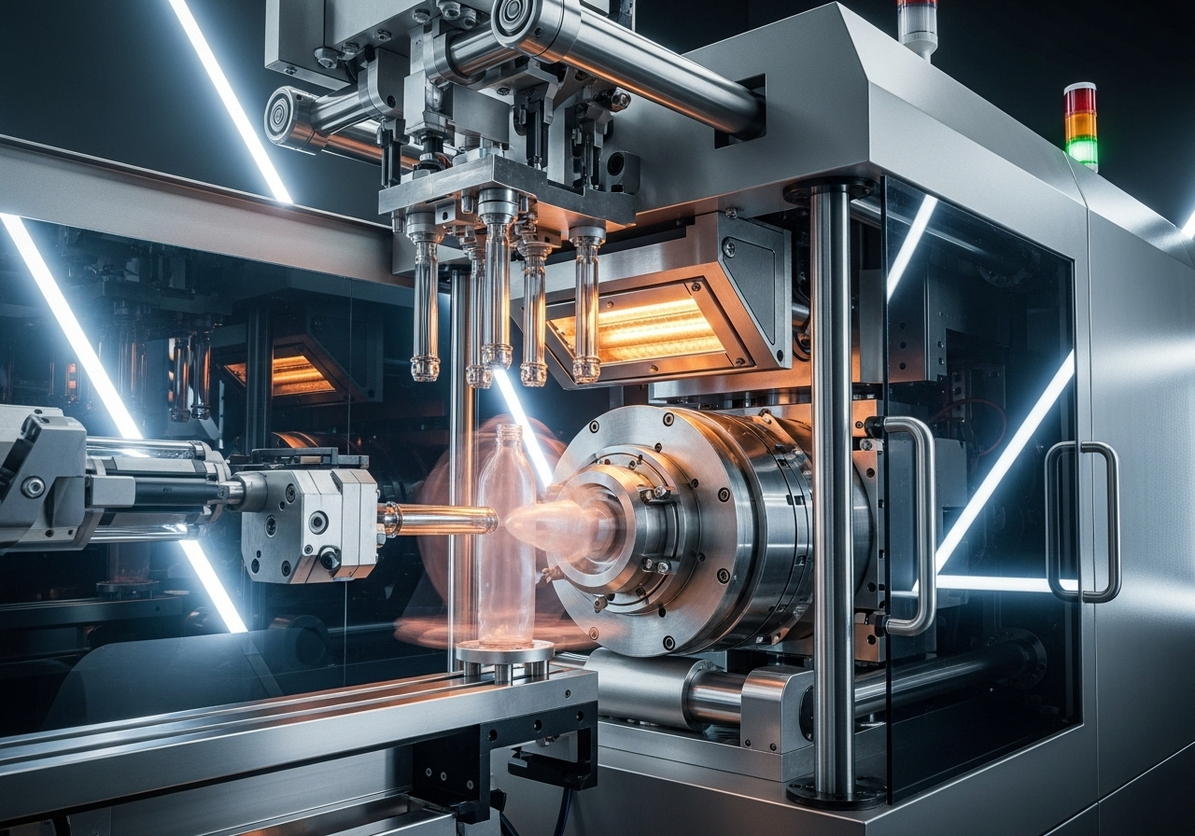

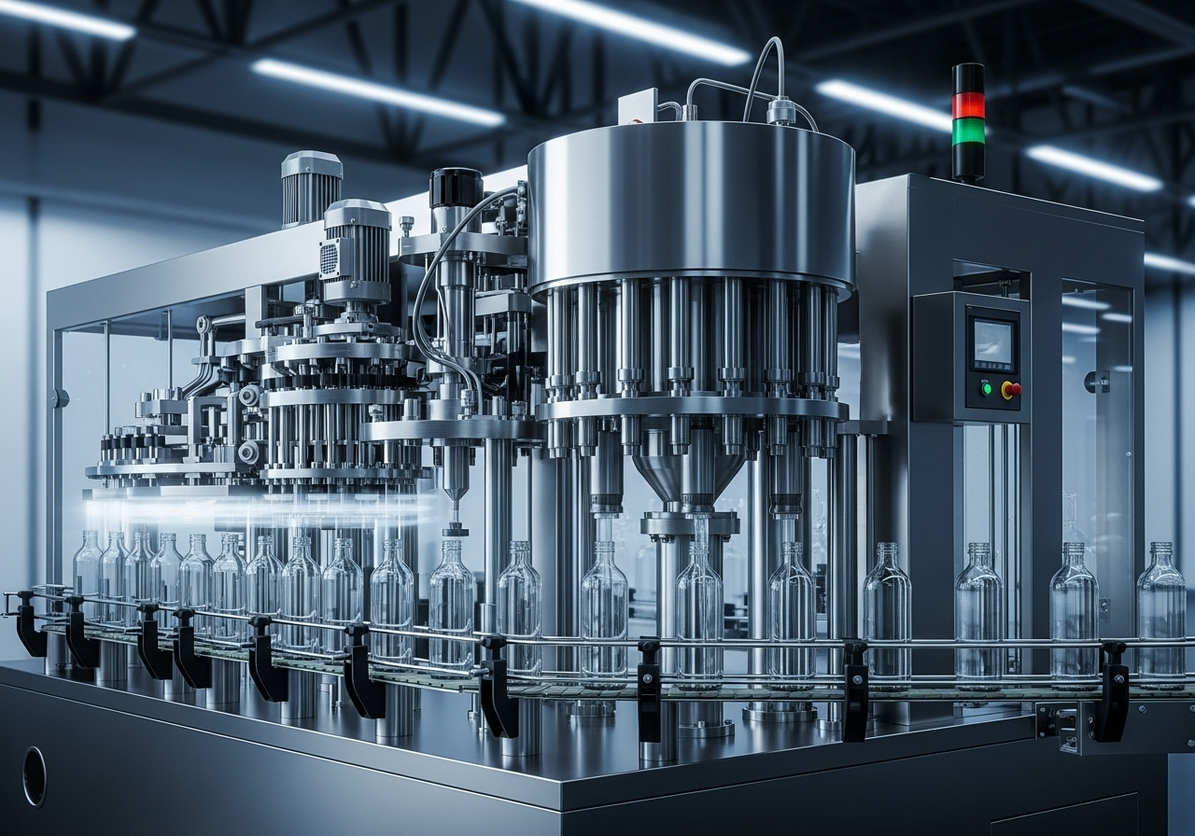

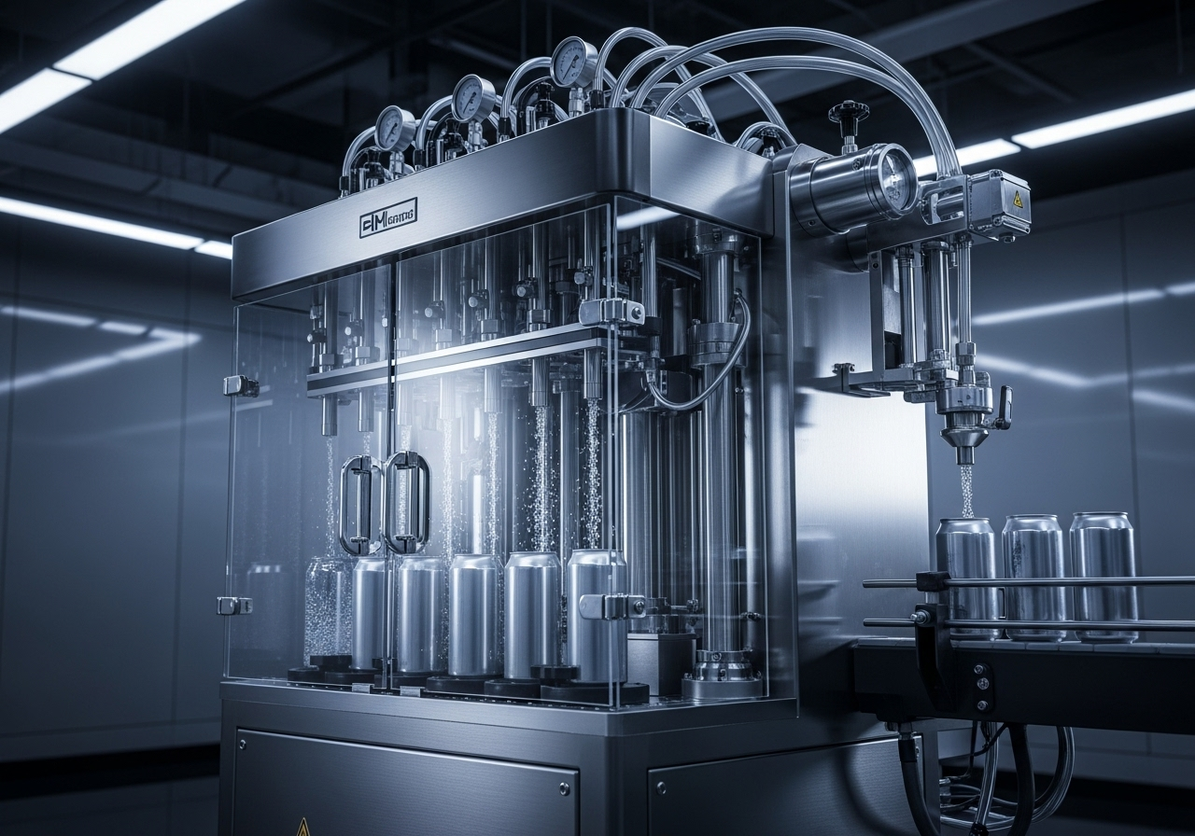

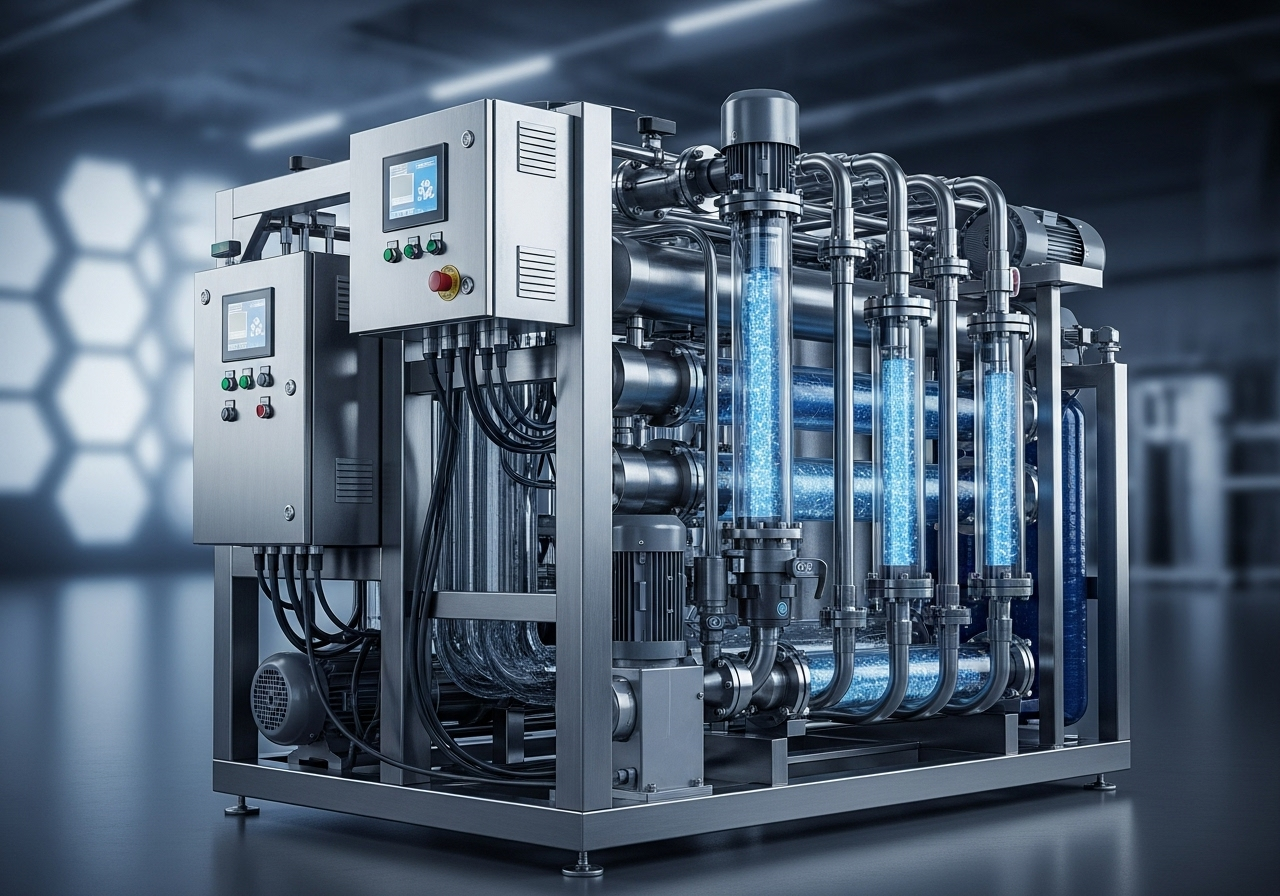

We kept it simple and matched each site’s real constraints. The seafood plant deployed a chamber-style unit with twin 8 mm seals and a moisture-tolerant pump configuration. We validated with 90–120 μm pouches, standardizing on two SKUs to keep purchasing under control. The tea exporter used nitrogen backflush to protect aroma, paired with a mid-size chamber and a removable filler plate to cut cycle time by 1–2 seconds. The kitchens picked the **compact ASFL vacuum sealer** variant to fit their counters and still reach −80 kPa reliably.

For branding and market fit, we called the Kandy setup a **food ASFL vacuum sealer** package internally—chamber, filler plates, and a simple gas kit—so procurement knew what they were buying without chasing part numbers. At all three sites, we spec’d service access from the front, and we tracked consumables cost per bag. The range settled at $0.04–$0.07 depending on thickness and shipping. Hardware cost per unit landed between $400 and $700, based on options and local taxes. Payback math penciled in at 4–7 months, varying by rework avoided and labor saved on re-packs.

Outcomes weren’t perfect, and that’s fine. The seafood site moved OEE from 62% into the 74–78% band over four months, with rework trending near 4%. Tea held scrap near 2% while keeping aroma notes clients cared about; they accepted a slightly slower cycle on gusseted bags. Jakarta’s kitchens reported stable 14–16 second cycles and fewer customer complaints about leaks. They still see the odd failure on overstuffed portions, which we’re tackling with portion-control cues. For our team, the result was practical: consistent seals, predictable costs, and room to grow with **ASFL** if volumes justify it.